THE GAS WORKS

In the mid nineteenth century the coal trade was at its height. Ships from the north east of England and Scotland poured into the Thames. Coal came into the wharves on the Peninsula for all sorts of reasons – some of it was used as a the source of the raw materials for chemical plants, but the main use was to fuel the boilers of the steam engines which began to provide power for the new factories. After 1880 coal was used to supply centralised power plants – like gas works, and later on electrical power stations.

(The Gas Works. The East Greenwich works of the South Metropolitan Gas Company was so big, and so successful that trying to write anything sensible about it is almost impossible – hence a number of authors have tried to write about it, and usually failed. The company produced a house magazine from 1904, originally ‘Co-partnership Journal’ and this continued in one guise or another until the works closed in the 1970s. The company minute books exist up to nationalisation in 1949 – but give very sparse details. There is some other information at LMA and a vast amount in the gas trade press. What archive remains – and most was thrown away – is at the National Gas Archive, or in boxes somewhere in Leicestershire, following the demise of the Bromley by Bow Gas Museum. Some material – in particular the ship models – are with Museum in Docklands, and some stored at Crossness Engines and/or the Thames Barrier. Reminiscence material is often hard to come by because the works was so big that workers never knew much more than their own small workplace. In particular mention must be made of the late Kay Murch, who has done so much against all the odds to preserve the memory of the gas works – in an era which has found little to say about it except that it poisoned people. Kay went to work at East Greenwich as a school leaver and in time found herself the only employee still on site – in January 2001 she was still there as the English Partnerships site manager. She was very proud of having saved the war memorial which now stands in John Harrison Way. The run-down process was dramatically illustrated in 2000 in a play put on in Greenwich by The Independent Photography Project ‘Throw out your Mouldies’ – the biggest gas works in the world ended up with just one person left. Do not listen to what the press says about the gas works at East Greenwich – while I am sure it left a legacy of pollution this was also th e pinnacle of gas works technology. They thought they were the best in the world, people were proud to work there and proud of what they produced – heat, light and public service).

e pinnacle of gas works technology. They thought they were the best in the world, people were proud to work there and proud of what they produced – heat, light and public service).

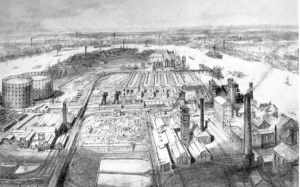

The South Metropolitan Gas Works grew to dominate the Greenwich Peninsula – it was built in the 1880s and was thus a late comer, sited on an area hitherto unused for industrial purposes. It was also very ‘modern’ – no gas works has been built in London since. It was the new, ‘super’, works through which the South Metropolitan Gas Company hoped to show the world what it could do.

George Livesey seems to have had no formal education. His childhood in the Old Kent Road left him with fond memories of local people and those who worked for his father. He signed the ‘pledge’ of temperance in his early teens along with a group of other young workers and, through them, began to attend prayer meetings. At the age of seventeen he attended the first meeting of the London Band of Hope. Temperance was to become his ‘other’ career and George maintained a lifetime close association with bodies like the Lord’s Day Observance, and the Good Templars. Somewhere along the line he picked up ideas from Christian Socialists, co-operators, and most significantly the Italian patriot, Mazzini.

(Sitting inside my computer is an unwritten biography of George Livesey – and again there are so many references that I could not begin to list them down. In 1989, I wrote ‘George Livesey’ published in London’s Industrial Archaeology, No.4. My M.Phil. Thesis Profit Sharing in the South Metropolitan Gas Company, M.Phil. Thesis, Thames Polytechnic, 1986 covers a lot of his work. Otherwise Derek Matthews 1984 Thesis on ‘The London Gas Industry’ PhD Hull gives a rather different view. One of the results of my known interest in Livesey was the ghost – first quoted in an article in The Guardian and subsequently the subject of a number of press stories (Fortean Times, date unknown, Daily Telegraph 27/4/1998, News Shoopper 6/5/1998 and interviews (including the John Dunn show in August 1999).)

A gas works may not seem the best ground from which to launch a crusade – but George was generally unstoppable. He was clever, good at everything he did, and could never resist a good cause – which ranged from the minutiae of gas works equipment up to grand schemes on the organisation of society itself.

By the 1870s George Livesey had moved the gas company on to the national stage. Through his negotiating coups South Metropolitan had taken control of a number of other local gas companies thus gaining a near monopoly in the area.

In the 1860s the two biggest gas companies in North London had both built large out-of-town works to provide bulk supply and enable them to close down small uneconomic works. Livesey decided that it was high time South Metropolitan did the same – but better – and in the early 1880s the site on the marsh was chosen.

BUILDING THE GAS WORKS

The new gas works was different to the industries which had already come to the Peninsula. As a large public utility, albeit a private company, it had a direct relationship with Parliament and the local authorities. It was not so concerned with any restrictions that Morden College, or other landlords, might impose, and it was big and powerful enough to impose itself on the area around it.

(The political background to the building of East Greenwich Gas works is a complicated subject which has never really been adequately covered. In my book on the Gas Works Sites of East London a bibliographic essay covers the earlier period. Derek Matthews Thesis covers some, but not all, of the issues. The serious student would need to read their way through issues of the contemporary gas trade press. W.Garton’s History of the South Metropolitan Gas Company, published in parts in Gas World during 1952 tells some of this story – but ends abruptly. There are also a number of Select Committee Reports – although some very persuasive evidence by Livesey means that gas company history is seen through his eyes rather than through research elsewhere – these include Gas (Metropolis Bill) 1860, Select Committee on Gas (Metropolis) Bill 1875, Select Committee on the Metropolitan Gas Companies 1899. A good contemporary source, written by a South Met. director, is L.W.S.Rostron, Powers of Charge. London, 1927)

The Gas Company cleared the Parliamentary permission to build the works on 140 acres of in December 1880. Discussions were already underway with the local authority on the new plant and its layout. It had been agreed that the purifying plant, thought to be the smelliest part of the works, should be placed on the northern most tip of Blackwall Point. This would ensure that smells were kept from Greenwich, while wafting over the Isle of Dogs. (See my The Millennium Site – Who built the Gas Works, Bygone Kent, 17/5, May 1996, pp. 287-290)

There were a number of objections to their plans – Coles Child’s executors wanted to build housing, as did Mrs. Fryer, another landowner. The owners of the dry dock on Blackwall Point claimed that the smell would damage the high-class paintwork they said they were doing. Parliament made some requirements before the works could be built – one was that they rebuild the river wall on the eastern bank, and provide Ordnance Draw Dock. The public footpath round the riverbank was closed.

None of this pleased ‘waterside people’ who continued to cause ‘difficulty’ by insisting on their old rights of way. (‘waterside people’ and other quotations are taken from articles in Co-partnership Journal ‘The Building of East Greenwich’, May 1911, Joseph Tysoe’s obituary in March 1913, and ‘Recollections of East Greenwich’ in May 1926. Also issues of Journal of Gas Lighting of 1881-4 where the construction of the works was covered on a regular basis). Docwra, the gas company’s contractors, dealt with this by placing ‘a gang of men’ to ‘divert this traffic’. Building work began very slowly. The contractors found access to the site difficult, describing it as ‘a cul de sac – and approaches thereto were not inviting’. Most of the site on which the gas works was to be built, in the centre of the marsh, was ‘market gardens of poor quality’. The builders were constantly reminded of this by the ‘sprouting of rhubarb’ throughout the site. Other reminders of the rural past were a few remaining cows which lived in a shed which ‘age had rendered rotten and insecure’. Others who thought they might have rights in the area were the gypsies for whom it was a ‘happy dumping ground’. With them the contractors were in a ‘constant state of warfare’. During one such running battle, Joseph Tysoe, the future works manager, only escaped serious injury when his assistant intercepted a heavy iron bar aimed at his head.

As work progressed, Docwra brought on site ‘extraordinarily powerful pumping apparatus’ and took borings to discover the state of the ground. Barge after barge came loaded with clinker and heavy rubbish to use as infill, but it took ‘a vast amount of effort to make a sensible impression on this wilderness’.

Slowly the works took shape. ‘Looming vast against the sky is the skeleton of the great holder’. This is the holder still to be seen today alongside the Blackwall tunnel approach road. It was thought it would ‘darken the sky like a mountain of iron’. The jetty too was taking shape, sinking as it was built. It was reported that it was ‘allowed to go as far as it would’ until it became ‘as firm as a rock’. (Livesey wrote a number of articles about gasholder construction – although the consensus was that it was his brother Frank who had to actually work out how to do it! They are in the gas trade press and in particular the 1903 Transactions of the Institution of Gas Engineers. Also, see Brian Sturt, Low Pressure Gas Storage, London’s Industrial Archaeology, No.2. 1980, Graham Ridout, Reliving the past at a bombed gasholder. New Civil Engineer, 12th February 1981, ‘East Greenwich Gas Works’ Archive, No.1. March 1994. There is also Malcolm Tucker’s definitive work on London gasholders in an unpublished report for English Heritage – however, anyone interested should watch out for one of his lectures).

East Greenwich gas works became world famous, and was once seen as an example of everything that was progressive in British industry. It must be ironic that in the 1990s we are looking at the gas works site in just the same way as its builders did.

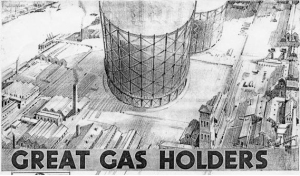

THE GAS HOLDERS

Ever since the gas works came to the Peninsula in the 1880s the structure which dominates the landscape has been the giant gasholder. For most of the time its even bigger neighbour stood alongside it. At twelve million cubic feet capacity, East Greenwich No.2 Gasholder was the biggest in the world when it was built in 1892. Two flying lifts were destroyed by an 1917 explosion and never replaced. (1917 This was the Silvertown Explosion which has been covered in a great deal of detail. In particular in a work by the late Howard Bloch, 1996, LB Newham. There are some dramatic accounts of it and how it affected the gas holder. For i.e. H.Townsend in Proceedings of Institution of Gas Engineers 1919). No.1. which still stands, is slightly older and smaller – small, in the sense that it was only surpassed by its companion. George Livesey believed in maximising both economy of construction and greatest storage capacity for ground area. The development of his ideas can be seen in its’ predecessor holders still standing at the Old Kent Road gas works site.

The holders were built without decoration as a symbol of all that was modern and progressive in British industry. The observer was expected to see them and be impressed, not only with their size but with their rationality. (Because of a remark made by Livesey in the 1903 Institution paper noted above I spent a lot time researching any link with the artist Christopher Dresser- whose views on industrial design were known to accord with Livesey’s reported remarks on the gas holder. I now accept, thanks to Malcolm Tucker, who is deeply into rationality, that the Major Dresser referred to is an American engineer and not an artist interested in industrial design. Pity)

CHANGE

For George Livesey the works was to be more than just another gas supply factory but was to embody the ideals, which he had cherished from boyhood. Within a few years of its opening a dramatic episode in industrial relations was to change both George Livesey and the South Metropolitan Gas Company in a fundamental manner.

In the late 1880s London was changing. Arguments about the government of London had led to the abolition of the Metropolitan Board of Works and, in late 1889, the election of the first London County Council. Ideas about public ownership of gas were being expressed- something which, naturally, Livesey did not approve of. (Livesey was heavily involved in lobbying the first LCC on the coal duty charges. Details in the contemporary gas trade press)

THE GREAT STRIKE OF 1889

1889 was the year of the great Dock Strike and the ‘new unions’. There had been trade unions in the gas industry since the 1830s and a bitter dispute in 1872 had led to legislation that made strike action illegal for gas workers . In the late 1880s Will Thorne and others began to organise gas workers north of the river on the issue of the eight-hour shift system.

(The great strike – this has been often, and inaccurately, reported in trade union histories – most notably by Yvonne Kapp in Eleanor Marx’ Virago 1976. Will Thorne of course also covered it in his autobiography My Life’s Battles, 1898– although close study of that document will reveal that he was outside London during most of the period in question. Both Derek Matthews and myself have tried to cover it in our respective theses and I have also written The Gas Workers Strike in South London, South London Record, No.4, 1989. At the time the whole episode was closely covered in the national press as well as Kentish Mercury and South London Press. After the strike Livesey wrote about it on every possible occasion – there is a vast archive of his work. Great detail was also given as evidence to the Royal Commission of Labour 1891-3)

The story of the 1889 strike has often been told. Negotiations proceeded with Will Thorne’s new union on a London wide basis but Livesey was determined that ‘outsiders’, as he termed the union, should not have any power in ‘his’ works.

Following what he described as a visionary episode on Telegraph Hill in Nunhead Livesey instigated a profit sharing scheme amongst the South Metropolitan. workforce. In this, and in the events that followed, it is sometimes difficult to reconcile Livesey, the deeply religious temperance worker, with the draconian industrialist. The Gas Workers Union objected to the profit sharing scheme because it included an anti-strike clause. They threatened action but, because they were unable to strike without breaking the law, had to persuade the workforce to hand in their notices.

Livesey sealed off the works in a state of siege and marched in ‘replacement labour’ recruited from a wide area and with the help of unsavoury professional strike breakers. The new workers came in by rail through Westcombe Park Station and proceeded down Blackwall Lane inside a police cordon, to the jeers of the watching crowd. Will Thorne was in Manchester and stayed there until it was clear that the company had won the dispute. Once inside the works the ‘new’ workers were not allowed to leave. Those that did get over the wall found there a hostile reception and fights and scuffles constantly broke out in Blackwall Lane. ‘Old’ workers held a bonfire party outside The Pilot pub in Riverway where they burnt an effigy of Livesey as the guy. Rumours of poor conditions inside the works, and, in particular, lice, began to spread. The great gasholder was watched constantly. If gas pressure fell then the company would have lost because contracts with local authorities – largely sympathetic to the strikers – would be broken. It did not fall and, in effect, Livesey had won. He kept the ‘new’ work force – since legally the action had not been a strike there was no need to take anyone back. Great hardship ensued amongst those who now had lost their jobs.

COPARTNERSHIP

(Co-partnership. Once again, this is covered both by myself and Derek Matthews in our respective thesis. In addition, Derek Matthews has produced an excellent article ‘The British Experience of Profit Sharing’ in Economic History Review, 2nd Series XLII, pp 440-482. There is a great deal of contemporary material on this and Livesey himself wrote about it exhaustively and on every possible opportunity (some of this is covered in the bibliography to my M.Phil. Thesis). There is a vast amount of material in Co-partnership Journal, albeit all extremely partisan. There were also four Government reports commissioned by the Board of Trade from W.Schloss in 1890, 1894, 1912, and 1920.)

Once the dispute was over Livesey began to expand. Any worker with ideas about trade unions was best advised to keep them to himself. The profit sharing scheme began to evolve into something that Livesey called ‘co-partnership’ and a whole structure of participation and involvement began to be built up. Workers could take any grievances to ‘Co-partnership Committees’ which could also recommend changes in a wide range of working practices, and involved themselves in decisions on the various funds – pensions, sickness and so on – managed by company representatives. Co-partnership committees were elected by the workers with an equal representation from management.

In the 1890s Livesey managed to get the company structure altered by a reluctant Board and House of Commons to allow three board members to be directly elected by the co-partners in the workforce. Livesey was nothing if not thorough. On most occasions he was prepared to follow through the logic of what he had done so long as it did not involve giving away any real power. In the years that followed he lectured and wrote constantly about his system. Immediately after the strike his only sympathisers were ‘The Liberty and Property Defence League’ – the liberty and property in question being their own – and the ‘Anti-Picketing League’. The other London gas companies found it more useful to keep in with Will Thorne.

Livesey gradually moved towards a group of idealists on the fringes of the Co-operative movement – the Labour Co-partnership Association.

In 1906 he was to be National President of the Band of Hope and continued to speak on platforms throughout the country on their behalf and for related causes which continued to provide audiences plus bands, flowers and acclaim. The knighthood – and his place in innumerable worthy causes and on Commissions after 1900 – may well have been as much to do with his temperance works as anything. For them there had never been anything to forgive.

“Band of Hope – my attempts to research Livesey’s temperance activities have been rather hampered by the lack of records – several key organisations lost documents in the Second World War, and by the extremely schismatical nature of the movement, Typically Livesey seems to have been a member of several different factions! First if all, George Livesey is nothing to do whatsoever with the Lancastrian guru of the Band of Hope, Joseph Livesey. George Livesey was in his own right a major figure in the Band of Hope and had been at their inaugural London meeting as a teenager. To read temperance records is to see a different Livesey – they see him as a temperance reformer who just happens to work for the gas industry and this is a whole side to him which has not been explored by labour historians who are looking for his anti-trade union roots. It is actually likely that his knighthood was for this rather than his work as a gas company manager. However thanks to John Beasley, a local historian who also happens to work for Hope UK)

EAST GREENWICH WORKS

How did all this effect East Greenwich? Alongside the main gate of the gas works stood the Livesey Institute – a meeting room, hall and theatre. Alongside it was the bowling green, and, in due course a War Memorial. To the south were the allotments and sports facilities.

Most of all, of course, there was the showpiece gas works – almost the biggest in the world, with every department aiming at nothing less than perfection. Dedicated public service to standards that were not only high but encompassed progress and modernity. If that standard was not always reached it was not for lack of saying so. By the time nationalisation came in the late 1940s the South Metropolitan workforce was proud and exclusive. To be a gas worker in Greenwich was to be something very special – better than any other gas workers – better, in fact, than anyone else.

(East Greenwich Works The best source still remains the House Journal, plus some reports and papers produced by the company for foreign visitors (Greenwich Heritage Centre has some of these, albeit in French and German. As for it being the biggest in the world – this claim was also made by Beckton Works and so who you believe really depends on which side of the River you live. In any case Livesey made sure that his holders were not only biggest in the world but big enough to be seen from Beckton)

George died in 1908 and his place as Company Chairman was taken by Charles Carpenter, an enthusiast for chemical weapons – a trade soon added to the East Greenwich repertoire. The Fuel Research Institute was Government owned and stood adjacent to the South Metropolitan Gas works. Much of its activity is still shrouded in mystery but its role was to do with the investigation of coal based chemicals and the use of coal as a fuel. A Second World War innovation of which they were proud was a smoke screen device.

Fuel Research. This was an important institute – one of the many research organisations in Greenwich of which we ought to be proud. Like most of the others this one was, unfortunately, focussed on warfare. I have a number of reports and booklists from the Institute which have been passed to me by various interested parties! Other information comes from a commemorative booklet produced at the end of the war by the Metropolitan Borough of Greenwich.

In March 1952 the Duke of Edinburgh, described as ‘a good looking young man who drove his large Austin Saloon’52 visited the station. They explained to him the wartime smoke elimination process as well as experiments on combustion in vortex chambers. He was shown the Calorimeter building for research in domestic heating, which was unique in the world and he met the blacksmith, the longest serving member of staff there. Herbert Morrison visited in 1946 and saw the smoke elimination process and also looked at products which could be obtained from coal and the research into domestic heating from coal.

COLLIERS

At East Greenwich South Metropolitan Gas Co. had their own collier fleet to bring the coal from the Newcastle and Blyth areas. Before the Second World War there were seven vessels- each of 2,000 tons capacity. Four were lost during the war – Brixton, which was mined, Old Charlton, dive-bombed, Effra torpedoed by an E boat and Catford mined. The fleet after the war consisted of Camberwell, Redriff, Brockley and Effra- A replacement Effra was described in 1946 as the last word in luxury as she entered the Thames with her first cargo of coal from Newcastle. She had what then was all the latest equipment -including an echo sounder.

(There is increasing interest in gas company collier ships but little written – beyond a report of lecture by the late Alan Pearsall, in Greenwich Industrial History November 2000. Brian Sturt does very good lectures on the subject).

ELECTRICITY

The only trouble with the great gas works was that it was the last one. By the 1880s gas was not new technology – although it put up a very good fight! The future was with electricity and an electric power station was very soon to stand alongside the gas works.

The East Greenwich tide mill had been almost the latest thing in 1803 – a sophisticated machine to harness the power of the tidal river. It had been overtaken by steam – power generated from coal. The gas works provided another means of power generation from coal. In the early 1890s the old tide mill was replaced by an electrical power station. There was no concept then of the giant power stations which have since grown up and there was no national grid. These early power stations provided electricity to quite small local areas. Many of them were started by the local authorities and many burnt rubbish – for example in Woolwich the local council had built its own power station to make electricity from local waste. In Greenwich a private company undertook this role.

THE FIRST POWER STATION

(The first power station – When I wrote this I knew very little about it. Most of what is here comes from plans, from some research published by Peter Guillery in a list of Thameside power stations (on which he does a very good lecture) and some press reports. It apppeared that the previously carefully kept archive of power station records had been junked following privatisation and no official record remained. Over the years since Greenwich Industrial History Society has been sent pictures and memories of this power station site)

The new power station built at what became known as Blackwall Point was built by the Blackheath and Greenwich Electric Light Co. It began to supply local people in 1900 by generating power using steam engines fuelled with coal delivered through a big new jetty. The Company’s name was changed to the South Metropolitan Electric Light and Power Company Ltd.

They called the new power station ‘The Powerhouse’. In 1906 it was extended and when it closed it had a capacity of 15,000 kW. In the 1930s South Metropolitan Electric had showrooms in Lewisham and Sydenham – and locally in Stratheden Parade at Blackheath Standard – almost, but not quite, rivalling the showrooms of South Metropolitan Gas.

In 1901 most of the millponds were still traceable despite having been filled with cinders. A bank ‘8ft or 10ft high’ surrounded the pond so that it could hold water to high tide level. It was thought that the bottom was below ground level. (Goad plans)

ANOTHER EXPLOSION

Just before Christmas 1906, there was a sad echo of the 1803 accident when Trevithick’s boiler had exploded. William Shaw and James Coombes were working on the power station boilers and were killed as the result of an explosion. Their bodies were blown to pieces, and beyond recognition.

Coombes lived nearby in River Terrace and was a fitter employed at the power station. Mr. Shaw, an inspector from the National Boiler and General Insurance Company, had been called in to examine a leaking drum on the boiler. A leakage of this sort was not unusual and was normally dealt with by caulking. This leak seemed to be very minor, somewhere in the joints rather than the plate of the drum itself. The boiler had been retested regularly. Mr. Shaw was looking for the site of a crack when the explosion occurred.

Both men were killed instantly – James Coombes was identified only by his clothes. The accident was probably caused by an old crack, not visible from the outside of the drum, which had been missed during testing. Later, at the inquest into the deaths members of the jury were clearly very shocked and upset by what they had heard. The original foreman was taken ill after hearing the first evidence and did not return. (Kentish Mercury)

The accident was reported in some detail, together with pictures, in the works magazine of the adjacent South Metropolitan Gas Company. It appears that employees of the gas company’s other works were invited to Greenwich to see the damage in order that ‘those who have charge of boilers. Realise more fully the extent of their responsibility’ – rather than, of course, to see how dangerous electricity was compared to gas! In light of the horrific injuries which were suffered by the two victims this sanctimonious action by the gas company was taking things a bit far!

(South Met. Gas reported the explosion in Co-partnership Journal of February 1907. At the time the gas industry had declared all out war on Electricity – anything power stations did was bad and had to be reported. This included claims that coal dust pollution from electricity was particularly dirty while gas works generated dust was good for you)

THE SECOND POWER STATION

The South Metropolitan Electricity Company had decided to replace the power station with a new one before 1939 and it was thus closed and demolished in 1947. Nationalisation overtook them before it was finished and the new Blackwall Point power station opened in 1952.

The power station will be remembered by many local people and it is therefore remarkable that it has proved impossible to trace any archive of this publicly owned site. The whereabouts of records known to have been held before electricity privatisation has become a great mystery.

The new power station was bigger, although limited by its narrow site. For this reason the administration and amenity block was built on the south side of Riverway – connected by an overhead bridge. Equipment used for river navigation was put on the roof of this block by the river authorities and ensured that it was not demolished but remained in a state of dramatic dereliction for many years.

A jetty was built for ships up to 3,000 tons and with facilities so that waste ash and dust could be loaded into barges. (the jetty is of course still standing and has recently been the subject of a proposed community project for preserved historic vessels). Three mills ground the coal into dust before it was fed to each boiler. Three turbo-generators worked to provide the power. In 1953 it was rated the eleventh most efficient power station in the country.

Six months after it closed in June 1980 a group from the Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society visited the site. They were able to actually enter one of the boilers and spend time in the coal handling plant. From the roof they noted ‘a magnificent view of the surrounding industrial landscape’ – who would have believed that soon all this would have gone and that the site on which they stood would remain derelict for the next twenty years.

Refering to the last statement about the Gas holders not being next to the river, if google map the peninsula it shows them in exactly the same position as the drawing, between the motorway and the river